This is part two of the second in a series of four posts about using library collections for the study of black history, literature and culture, in Britain and abroad. We would love to hear your comments and questions about the posts: please tweet us @GCWLibrary, email us at library@lincoln.ac.uk, or tell us your thoughts in the comments section at the end of the post.

Early Printed Books by Black Authors

There are many ways in which early printed books can be used as a source for Black history in the early modern period. One step is to look for early printed books by Black authors—one book I particularly recommend if you are interested in this line of research is Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, a collection of papers which explores black history from a number of angles, including renaissance conceptions of race, African experiences at European courts, slavery and emancipation, and cultural representations. Two chapters focus on the career and writings of black intellectuals: Juan Latino, an Afro-Hispanic poet and professor of Latin who wrote an epic poem on the battle of Lepanto, the Austrias Carmen (1573) as well as three volumes of poetry; and Afonso Álvares, the author of four plays about the lives of the saints.[1] Neither of their works (as far as I can tell in searching for their names and the titles) are found in Early European Books, but a search for Juan Latino in the Universal Short Title Catalogue (USTC), does bring up a record of two volumes of poetry, from 1573 and 1576.

Finding Black authors in the early modern period leads us to issues of early modern ideas of race. Scholarship on race and racial thinking has sometimes emphasised a difference between the ideas of race held by pre-modern versus modern societies.[2] In her discussion of Renaissance European stereotypes of Black people, Kate Lowe argues that the capture and sale of Black Africans in the European slave trade, beginning in the 1440s, led to the predominant stereotype that a person with black skin was (or ought to be) a slave. At the same time, someone like Juan Latino, a former slave who participated in European cultural life and norms, might, in Lowe’s words, ‘be accepted as ‘honorary’ Europeans who just happened to have black skin’.[3]

In the Renaissance and early modern period, definitions of blackness and whiteness were fluid rather than fixed, and you might imagine, determining how an individual saw themselves is not always easy.[4] The life and works of Johannes Leo Africanus, (c. 1494 – c. 1554?), born al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan, can be used demonstrate the changeability and flexibility of such definitions, then and now. He was of Berber descent, a speaker of Arabic, Berber, and Italian who also wrote Latin, and a convert from Islam to Christianity and back to Islam again. His life and works were once thought to be the inspiration for Othello, one of the most famous black characters in Western drama. Even as they have moved away from arguing for a direct link between Othello and Leo Africanus, Shakespearean scholars continue to discuss the two together to understand early modern attitudes towards race and religion.[5]

al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan, often called Leo Africanus, was born in Muslim Granada and after this kingdom fell to Spanish Christian forces, his family fled to Fez, where he grew up. As a young man he travelled around Africa and served as diplomat. After being captured by Spanish pirates, he spent about ten years of his life in Italy, where he was baptised and acquired the Latin name by which he is usually known. He drew on his travel experiences and education in Arabic to write Libro della Cosmographia dell’Affrica, a description of the geography of northern and western Africa, particularly the Maghreb. His description of African culture, religion, and language proved popular, and his work was republished and translated into several languages, including English.[6] Searching for Leo Africanus in Early European Books (EEB) brings up several of these translations.[7]

Through European Eyes

Keyword searches for ‘Africa’ and ‘Ethiopia’ in EEB and Early English Books Online (EEBO) can take you in some interesting direction in looking for European perspectives on Africa in the early modern period. These search might lead towards the work of Alvise Cadamosto, a Venetian merchant who published an account of his exploration of West Africa during his service with Prince Henry the Navigator, Joao de Barros who wrote an account of Portuguese exploration of the coast of Africa until 1498, including descriptions of the Gold Coast, Benin, and the Congo; and Francisco Alvares, who wrote a description of Ethiopia. These accounts and others often tell us more about contemporary European values than about early modern African realities.[8]

In addition to geographic and cultural descriptions, limited as they can sometimes be, there is a third area in which early printed books can be particularly interesting for studying black lives and experiences: writings for and against slavery. The trade in black African slaves was growing at the same time as the printing trade, and we can use early printed book databases to track the earliest reactions and debates, including an anonymous pro-slavery pamphlet published in 1680, Certain considerations relating to the Royal African Company of England, which can be found in EEBO. Seventeenth-century and early eighteenth century English opposition to slavery can also be explored, including the work of the London merchant Thomas Tyron (1634-1703) Friendly advice to the gentlemen-planters of the East and West Indies (1684), who criticised the corruption, immorality, and cruelty of Caribbean planters.[9] It is also possible to use EEBO to explore early anti-slavery sentiment in North American, including An exhortation & caution to Friends concerning buying or keeping of Negroes (1693), which was one of the earliest anti-slavery tracks printed in North America.[10] Samuel Sewall, notorious as a judge in the Salem witch trials, was later in life the author of an early colonial anti-slavery tract, The Selling of Joseph (1700).[11]

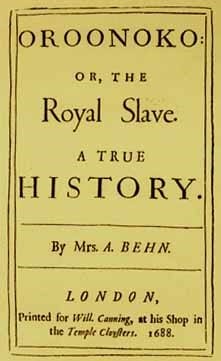

Slavery featured in early modern novels, such as Oroonoko: or, The Royal Slave (1688) by the English writer Aphra Behn (1640-1689). Behn was a novelist, playwright, poet, and spy, and a professional writers. She spent a brief period of her life in Surinam, where she would have seen planation slavery; these experience may have provided some of the inspiration and material for her novel.[12] Oroonoko tells the story of an African prince captured and sold into slavery, and in it Behn touches on major issues of her day such as slavery, kingship, class, and women’s roles.[13]

Final Thoughts

In the first part of this post, we looked at how to search Early European Books and Early English Books Online. This second part of the post has aimed to give you some suggestions for exploring Black history in early printed books. As this post has shown, some of this material has to be handled with an understanding of its context, but there is a wealth of it out there.

Further Reading

Earle, T.P. and K.J.P. Lowe (ed), Black Africans in Renaissance Europe (Cambridge, 2005)

Davis, Natalie Zemon, Trickster Travels: A Sixteenth-Century Muslim Between Worlds (New York, 2007)

Gould, Philip, and Vincent Carretta, Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic (Lexington, 2015)

Guasco, Michael, Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Philadelphia, 2014).

Habib, Imtiaz H., Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500-1677: Imprints of the Invisible (Aldershot, 2008)

McKnight, Kathryn Joy and Leo J. Garofalo (Eds), Afro-Latino Voices: Narratives from the Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic World, 1550-1812 (Chicago, 2009)

Spicer, Joaneath A. (ed), Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (Baltimore, 2012)

Wright, Elizabeth R., The Epic of Juan Latino: Dilemmas of Race and Religion in Renaissance Spain (Toronto, 2016)

Notes

[1] Elizabeth R. Wright, The Epic of Juan Latino: Dilemmas of Race and Religion in Renaissance Spain (Toronto, 2016) This is available in the library collection. If you are interested in a translation of the Austrias Carmen from the original Latin into English see, Holt Parker, ‘Juan Latino (Johannes Latinus). On the Birth of His Serene Highness Prince Ferdinand’ Renaissance Latin Poem of the Week [blog] (2013), available from: http://renaissancelatinpoemoftheweek.blogspot.com/2013/04/5-juan-latino-johannes-latinus-on-birth.html [accessed 22 October 2018]. A published translation is available in Elizabeth R. Wright, Sarah Spence, and Andrew Lemons, The Battle of Lepanto (Cambridge, 2014).

[2] Scholarship abounds on these questions. Among the works in the library, see Jessica Delgado and Kate Moss, ‘Religion and Race in the Early Modern Iberian Atlantic’, in The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Race in American History ed by Paul Harvey and Kathryn Gin Lum (Oxford, 2018), 42-57; and Michael Guasco, Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Philadelphia, 2014).

[3] Kate Lowe, ‘The Stereotyping of black Africans in Renaissance Europe’, in Black Africans in Renaissance Europe ed by T.F. Earle and K.J.P. Lowe (Cambridge, 2005), 17-21. The quotation is at p 18.

[4] Kate Lowe, ‘The Black African Presence in Renaissance Europe’, in Black Africans in Renaissance Europe ed by T.F. Earle and K.J.P. Lowe (Cambridge, 2005), 10.

[5] Jonathan Burton, ‘‘A most wily bird’ Leo Africanus, Othello, and the trafficking in difference’, in Post-colonial Shakespeares ed by Ania Loomba and Martin Orkin, (1998), 43-63.

[6] Sandra Young, ‘Early Modern Geography and the Construction of a Knowable Africa’ Atlantic Studies 12:4 (2014), 412-434. On the subject of translation of his works see Oumelbanine Zhiri, ‘Leo Africanus and the Limits of Translation’ in Travel and Translation in the Early Modern World ed by Carmine G. Di Blase (Amsterdam, 2006), 175-186. On his biography and the context of his life, see Natalie Zemon Davis, Trickster Travels (New York, 2007).

[7] The English translation of 1600 is available via the library website. Leo Africanus, The History and Description of Africa and of the Notable Things Therein Contained : Written by Al-Hassan Ibn-Mohammed Al-Wezaz Al-Fasi, a Moor, Baptised As Giovanni Leone, but Better Known As Leo Africanus. Trans. by John Pory (Farnham, 2010).

[8] Lowe, ‘The Stereotyping of Black Africans’, 18.

[9] Philippe Rosenberg, ‘Thomas Tyron and the Seventeenth-Century Dimensions of Antislavery’, The William and Mary Quarterly 61:4 (2004), 609-642.

[10] Katharine Gerbner, ‘Antislavery in Print: The Germantown Protest, the “Exhortation,” and the Seventeenth-Century Quaker Debate on Slavery’ Early American Studies 9:3 (2011), 552-575.

[11] William Bedford Clark, ‘Caveat Emptor: Judge Samuel Sewall versus Slavery’, Studies in the Literary Imagination 9:2 (1976), 19-31.

[12] Mary Ann O’Donnell, ‘Aphra Behn: The Documentary Record’, in The Cambridge Companion to Aphra Behn, ed. by Derek Hughes and Janet Todd (Cambridge, 2004), 1-11.

[13] Laura J. Rosenthal, ‘Oroonoko: reception, ideology, and narrative strategy’, in The Cambridge Companion to Aphra Behn, ed. by Derek Hughes and Janet Todd (Cambridge, 2004), 151-165. The novel was later adapted into a successful play by Thomas Southerne, Oroonoko: a Tragedy, which can also be read on EEBO.